NOTE: This case study was originally published in two parts in 2010 on a blog about medical checklist design. It has since been revised and combined.

I was traveling in late 2007 and happened to pick up the New Yorker issue with Atul Gawande’s The Checklist. I’m a bit of a clarity geek, so the idea of putting simple, critical information in front of surgeons to deliver better outcomes was immediately intriguing.

A couple years later, we had a some down time in the studio so I approached the Surgical Clinical Outcomes Assessment Program (SCOAP) here in Washington state to learn more about the organization and their surgical safety checklist project. After a few initial conversations, my team and I began redesign of the SCOAP Surgical Checklist as a pro bono project.

BEFORE: Two versions of the SCOAP Surgical Checklist from 2009.

AFTER: The checklist was redesigned as a large printed poster, a PDF for electronic display, and a letter-size black and white version for use on a clipboard.

Diagnosis

At Emphatic, we begin all projects with a diagnostic phase. This enables us to understand the context, evaluate the problem or opportunity, and prescribe an appropriate solution.

Research

Background and context

To get oriented, my staff and I conducted searches to find and study:

Literature on medical checklists (implementation, efficacy, and design)

Literature on the design of aircraft checklists

Samples of medical checklists

Organizations spearheading medical checklist initiatives (e.g., WHO)

Medical checklist implementation manuals

Other medical checklist communications

We also looked at historical versions of the SCOAP checklist and other SCOAP content.

User and stakeholder research

It is helpful to learn why things are the way they are, so I interviewed Justine Norwitz, then SCOAP's Strategic Development Director, to better understand the process and rationale that led to the design of their existing checklist.

Next, I conducted stakeholder and user interviews with surgeons and nurses at representative institutions in Washington state (small, large, rural, urban, clinics, and teaching hospitals). The goal was to gather information about their experiences using the SCOAP Surgical Checklist, uncover problems or concerns, learn about modifications they made, and ask for their insights about possible improvements.

A few of the more interesting findings:

No consistent role at an institution was responsible for modifying or producing their checklist (the people responsible ranged from Chief of Surgery to nursing personnel to administrative staff)

Some sites had tried letter-size pages but all were using a poster version at the time of our initial interviews

No sites marked check boxes or included the checklist in the patient record

Many sites reported issues with the debriefing process

Teaching hospitals had unique issues (e.g., lead surgeons often leave prior to closure, so debriefing was a challenge)

We prefer to conduct observational research as well, but limited time prevented us from seeing the checklist in action in operating rooms. Fortunately, we had high quality information from the interviews and video of the checklist being ‘run’ by a surgeon, so we were able to move ahead with confidence.

What about training?

The SCOAP surgical checklist had been widely adopted in a short period of time, in part because it has been championed by individual surgeons in influential institutions. I was surprised to learn that few of the institutions I interviewed had a formal training program to help staff understand and follow the checklist protocol. This stood out as a key unexplored opportunity -- to create a framework that institutions can use to train surgical teams and other stakeholders on surgical checklist adoption and use.

Analyzing the content and format

Finally, it was time to examine the content and structure of the actual checklist. Here's what we looked at:

Information. We created an information inventory by cataloging and categorizing the existing content. That process enables us to understand and prioritize the core pieces of information -- who does what, when, under which circumstances? -- as well as ancillary information like title, logo, copyright, etc. We used the inventory as a foundation for all subsequent visual design choices.

Visual design. We evaluated the existing design in light of our experience, established best practices, and the literature on checklist design.

Updated content. Last in this phase, we looked at how to best incorporate proposed changes from SCOAP and checklist users.

Findings

The SCOAP team had done well overall: meaningful task items had been identified and vetted and the effort had support from a coalition of stakeholders. But we also saw that the SCOAP checklist could be significantly improved in three ways:

Make content easier to navigate.

Offer facilities a choice of format.

Make it easier to customize the checklist.

Recommendations

Streamline content

The language and flow of tasks was good but would be improved by simple changes:

Remove Yes, No, and N/A check boxes (no facilities were writing on the checklist).

Simplify labels; e.g., use “before” rather than “prior to.”

Remove the logo and add the SCOAP name to the footer.

Make footer content small and move it to the bottom to expand space for tasks.

Create several versions and let facilities choose

Most institutions used a poster of the checklist in the operating room, but a hand-held checklist could work better at some sites because of limited wall space or team preference. Our solution:

Create separate clip-board and poster versions and optimize the text size and the flow of content in each format.

Create a distinct version without pre-operative safety checks for facilities that perform those checks in a separate location and/or use a separate checklist for those tasks.

Give people a file they can edit and help them do it

Some of the people we interviewed were not aware they could modify the SCOAP checklist to meet the needs of their individual institution. Implementation instructions invited facilities to “customize the checklist with the input of your team members, but don’t remove any of the safety steps already listed on the Checklist.” But no instructions were provided to help people make changes and the checklist file was a PDF, a format that many people would not be able to edit. Our solution:

Create editable Word layouts for each of the final four checklists (in addition to the PDFs delivered for print and screen use).

Write easy-to-follow instructions to help facilities edit the SCOAP checklists.

Address visual flaws to improve usability

Our review identified several visual quirks that would made it more difficult for readers to easily read and navigate the checklist. Some of the key problems were:

Inconsistent list orientation. Lists of task items were presented as both horizontal and vertical lists.

Roles treated inconsistently. Role names were shown in several different sizes, sometimes inside parenthesis at the end or the beginning of headings, and sometimes within task items — very difficult for people to scan for their role!

Alignment undermines the purpose of the text: Because section titles were centered, the step numerals were not in a consistent position (they shifted left and right on the page) and were hard to distinguish quickly because they sat in the middle of other text.

Visually complicated: The use of gray shading was inconsistent (sometimes used for headings, sometimes used to highlight every other line in a list). That, combined with large dark areas and black lines around all the rows columns made the document feel complicated.

A large logo and lengthy footer reduced the space available for task items.

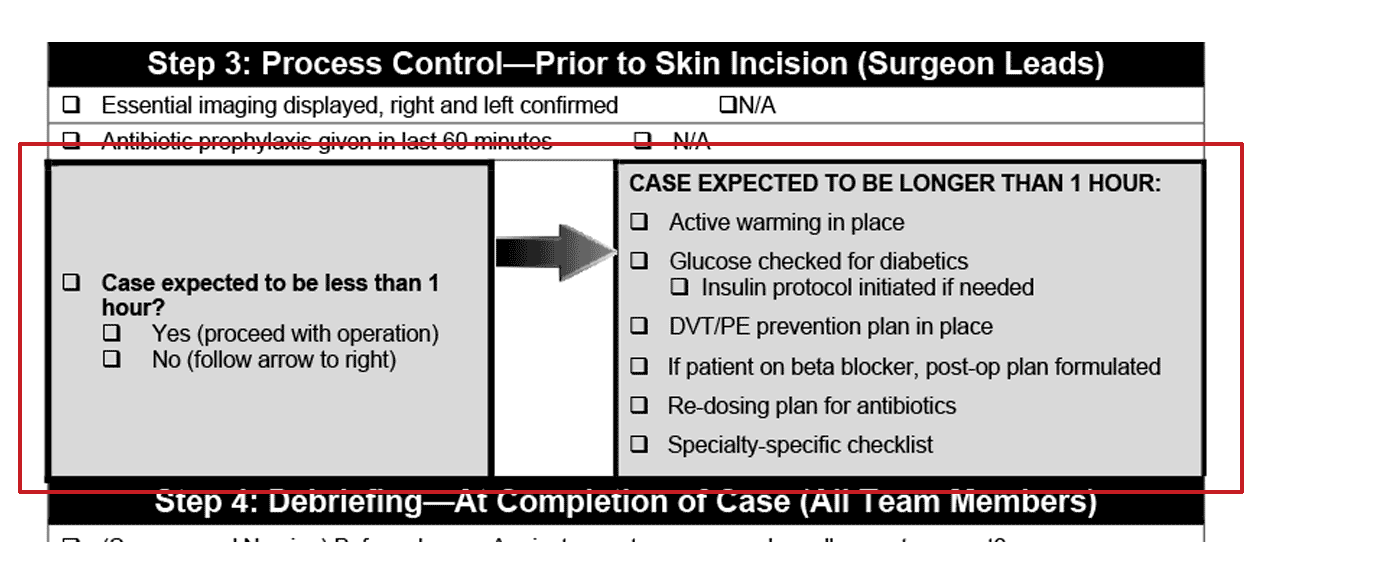

Boxes and arrows disrupted flow: One version of the original checklist tried to present one path for short surgeries and a different path for all others, but a heavy line around two boxes in the middle of the page (plus a large dark gradient arrow) grabbed too much attention and made the overall flow of the checklist hard to follow. Also note that the box labels (“Case expected to be…”) were styled inconsistently, so it was not clear at a glance how the content in the boxes was related.